The merchant of Venice

(2004, by Michael Radford)

Alberto Angelini

(Machine Translated by Google) – The desire for revenge, the represented and fully expressed desire to destroy an opponent, the source of so much humiliation. This is the underlying motif of Shakespeare’s beautiful and shady comedy The Merchant of Venice ; a text dear to psychoanalysis and visited by Freud himself. Precisely in one of the numerous sessions of the Psychoanalytic Society of Vienna, which often touched on themes of literary criticism, the young Otto Rank, in 1910, took the floor to illustrate a poetic example of a slip of the tongue, which he himself identified in this work. . Sigmund Freud greatly appreciated the intervention, to the point of adding it, in 1912, in the fourth reprint of Psychopathology of everyday life and to insert it, in 1915 in the Introduction to psychoanalysis.

The theatrical story is well known: Bassanio, to courtly court the young heiress Porzia di Belmonte, borrowed 3000 ducats from his merchant friend Antonio. The latter, rich but, at that moment without cash, asks Shylock, a Jew and, as such, the victim of bitter and recurrent humiliations by Antonio himself for the money. Shylock, who hates the merchant of Venice and desires revenge, hiding, offers the money on one condition: if Antonio does not return the money within three months, he will have to pay with a pound of flesh from his body. Bassanio at first advises his friend not to accept, then, thinking of Antonio’s enormous wealth invested in maritime cargoes, he capitulates and leaves to reach his beloved. Portia, tied to a paternal oath, will be able to marry only the one who, among three caskets, gold, silver and lead, will be able to choose the one that contains her portrait. Everyone fails, attracted by precious metals, but Bassanio chooses lead and conquers Portia. Meanwhile, Shylock’s daughter escapes with a Christian, also stealing money from her father. When he learns that Antonio cannot pay the debt, harboring his coveted revenge, he angrily demands his pound of flesh. It will be Porzia, disguised as a lawyer, to save Antonio with a legal technicality, while Shylock will end up deprived of all assets and forced to convert to Christianity. Rank’s slip occurs when Bassanio has to choose between the three chests. Having finally found in him the suitor she loves, Portia fears that he may be mistaken. She would like to communicate her love to him, but she is prevented from doing so by the oath. Faced with this inner conflict, the poet makes her say:

… I could guide you

To choose right, but I would fail to vote;

I don’t want that; you could therefore lose me;

And in doing so, you would make me repent

Not having failed to vote. Oh, your eyes

That in looking at me so they divided me!

Half are yours, the other half is yours …

Mine I meant ; but if mine also yours,

And so all yours.

She communicates so openly what she would only like to mention to him, because indeed she should keep silent about it; that is, that she is already all his and she loves him, calming the uncertainty of the lover and the identifying tension of the spectator, regarding the outcome of the choice. Freud was evidently struck by the mythical dimension of the situation. Not only did he use those lines to support the theory of slips; but, in 1913, he wrote a short article entitled The reason for the choice of caskets , taking a cue from the scene of Shakespeare. In summary, the Freudian hypothesis is that the caskets represent female figures and that we are faced with the choice that a man makes between three women. There are, then, many similarities with other mythological and fairy-tale situations. Shakespeare also tells the story of the old King Lear who wants to divide the kingdom between his three daughters while alive and chooses Cordelia, who unlike Gonerilla and Regana does not express his love in words. Paris, between Hera and Athena, indicates Aphrodite, who is the most beautiful and the most silent. Cinderella, chosen by the prince, is the most modest of the three sisters. This reluctance and silence are, by Freud, compared to the lead of the casket that contains the portrait of Portia. In fact, Bassanio says:

Thy paleness moves me more than eloquence

( plainess according to another version)

Your pallor (or your simplicity)

It moves me more than eloquence.

Gold and silver are “noisy”, while lead is “dumb”. The silence of Cordelia and Aphrodite, the hiding of Cinderella, the modesty of lead are, in Freudian terms, dream symbols of death. The one chosen among three women, or among the three caskets, corresponds, symbolically, to the third among the Fates: Atropos, the inexorable. The reason for the choice represents a reactive training, or rather a conversion into the opposite. It is a rebellious substitution that supports wish fulfillment. Where one has to obey by force and is a victim of destiny, one can choose; and she who is chosen is not the terrible, but the most beautiful and desirable of women.

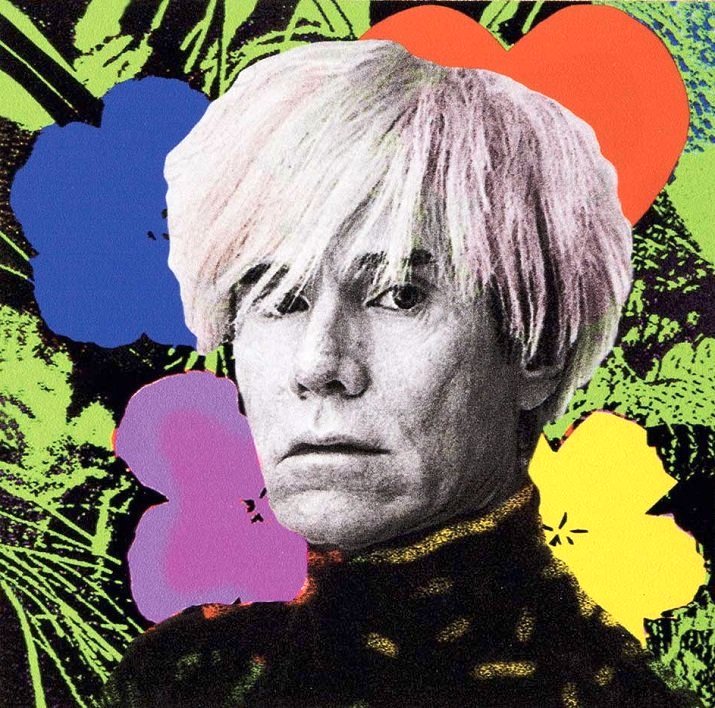

Radford’s film only partially touched the many depths of Shakespeare’s dark comedy. Joseph Fiennes, the handsome Bassanio, offers a mannered acting, which dominates the whole atmosphere of the Belmonte palace. An African prince, Bassanio’s competitor, looks like a television caricature and the same happens for the other suitor for the hand of Porzia, moreover lively represented by Lynn Collins. The situation is different for the other interpreters. Jeremy Irons, Playing Antonio, almost does not speak during the process of deciding his life, but conveys the extreme anguish of that situation with his attitudes and body tension. Al Pacino offers a great new version of Shylock. In this character, the poet maximally expressed his art. As observed by Lev Vygotsky, founder of the “Historical-Cultural Psychological School”, and adherent of the Moscow Psychoanalytical Society, in Shakespeare’s tragic heroes, far from delineating defined characters, opposite sentiments converge. We spectators understand the persecuted and humiliated Jew’s desire for revenge; we can also identify with the father who discovers himself betrayed by the same daughter, but at the same time we can’t stand his murderous intent towards Antonio. In the other film editions of The Merchant of Venice and in the majority of theatrical performances, the famous monologue of the usurer, “If you prick us, don’t we bleed? If you tickle us, don’t we laugh?” was generally offered in the form of a submissive lament. Al Pacino turns it into a long cry of rage. The furious rage of oppressed man, the desire for revenge of an entire people. A painful and grandiose feeling that no cinematographic interpreter of this character had before so masterfully approached.

Published in Eidos magazine, n.2 / 2005.